November 26th 2023.

Next club meeting Monday 4th December 2023.

- Subject - Members

Evening

The activities will be as follows:

1.

A coin quiz, be sure

to bring along a pen!

2.

Members to bring along one or two items

that for some reason are considered special (e.g. recent acquisition, a long

sought after piece, an unusual find, an oddity etc.).

A

brief written explanation as to why the piece is special

to you.

3.

Christmas buffet!

Meetings are held

at the Abbey Baptist Church, Abbey Square, commencing at 7.00 p.m.

Notices

·

Please continue thinking about Short Talks for January,

Auction lots for March and ideas for our 60th in May.

·

Please consider whether you could join the committee,

we WILL have vacancies come June.

·

The Xmas lunch is on 9th December at the

Bull at Streatley, please get in touch if you wish to come and haven’t already

signed up.

November Meeting

Our

November talk was by Mick Martin, who stepped in for Neil who was unfortunately

unable to give his talk due to illness. I am informed he is on the mend and we will have his talk some time next season.

Apologies

were received from Neil, Tony, Graham and David. John pointed out that if you

haven’t paid your subs then you will no longer receive the newsletter.

John

introduced Mick, although in truth he did not need any introduction, having

been Chairman of the club. In previous years he has delivered six full lectures

and eight short talks in addition to providing eleven short papers. Tonight he was talking on ‘Tokens and Medallions of the Monneron Brothers’.

Mick pointed out that a lot of the tokens were more like medallions and actually told a lot of the story of the French Revolution. They were complicated designs full of symbolism and revolutionary slogans, rather than advertising tokens. But first a bit of background to set the scene.

In the late 18th century there was very little coinage in England or France, though the reasons for that were very different in each of the countries. In Britain it was governed by the price of bullion, which meant that silver and gold coins were worth more when melted down, so there was no point in making them. The government had little regard for copper coinage and consequently there were never enough supplied to meet demand. In France, the reason they had no coins was because the country was essentially bankrupt, having spent so much money on Wars, principally in America. One person determined to remedy this situation was Matthew Boulton.

Boulton had an interest in coin production as a business. He realised that to be really successful you would need to mechanise the process and he did have a minting machine. Amongst other problems, you would need to be able to produce lots of dies quickly, since the average die would wear out after only two days in his machines. Also, in terms of design, you needed anti forgery devices and very good engravers. He visited Paris in 1786 on other business but also visited the Paris mint, who had already solved most of the problems and had good engravers. Having now got a plan he went back to London for the big one, producing copper coins for Britain. In this he was spectacularly unsuccessful. So he tried his luck in France, where paper money (assignats) were being used and were very unpopular, having no intrinsic value. Sadly, he met with the same lack of success.

This meant that he now had a big problem for his proposed coin business, a lack of backers and hence, a lack of finance. Reluctantly, he decided the only way out was to make tokens rather than state issues of coins. Looking for markets, he realised that in addition to the UK there were opportunities overseas, including in France. In this he was successful, his French agent managing to secure a contract with the Monneron brothers to produce tokens.

This could have been the kiss of death for the business, since the UK was still very nervous about anything to do with France following the Revolution, which many people thought could happen in Britain. So serious was this worry that some British reformers were charged with treason. Mick explained the politics of the situation by explaining how the revolution played out, it wasn’t all guillotines from the start. Firstly, there was the storming of the Bastille in 1789, and the National Assembly came into being, which formally removed powers from the King. Law and order did not break down until three years later, with the storming of the King’s Palace (Tuileries) when the bloodbath began, after the creation of the First Republic. Boulton was able to carry out his business in the hiatus between.

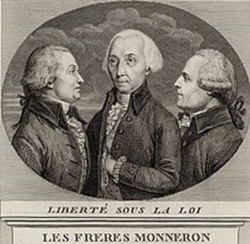

Mick

then went on to explain who the Monneron brothers

were. They came from a large rich family (thirteen in total) but the ones of

interest to us were merchants of sorts, wheeler dealers who had had successful careers

both overseas and in France. Not only did they survive the Revolution but held

positions in the National Assembly. Three of the brothers formed a bank in 1790

and one of them (Joseph) even had a licence to strike coins. Matthew Boulton

produced patterns to show to the brothers demonstrating his abilities. They are

very rare and Mick has only seen pictures but Boulton

also produced two medallions. The first was for Jean Rousseau who produced

books on reform, principally one called ‘Social Contract’. Indeed

some considered that his work helped lead to the Revolution but Mick didn’t

accept that. The second was for the Marquis de la Fayette, a national hero from

the American wars, commander of the National guard and a member of the National

Assembly.

Mick

then went on to explain who the Monneron brothers

were. They came from a large rich family (thirteen in total) but the ones of

interest to us were merchants of sorts, wheeler dealers who had had successful careers

both overseas and in France. Not only did they survive the Revolution but held

positions in the National Assembly. Three of the brothers formed a bank in 1790

and one of them (Joseph) even had a licence to strike coins. Matthew Boulton

produced patterns to show to the brothers demonstrating his abilities. They are

very rare and Mick has only seen pictures but Boulton

also produced two medallions. The first was for Jean Rousseau who produced

books on reform, principally one called ‘Social Contract’. Indeed

some considered that his work helped lead to the Revolution but Mick didn’t

accept that. The second was for the Marquis de la Fayette, a national hero from

the American wars, commander of the National guard and a member of the National

Assembly.

The

first token to be issued was the two sols (florin size) which contained several

revolutionary ‘signals’. We see Marianne, who

signifies Freedom, Equality and Justice, seated on a tablet which reads ‘The Rights

of Man’, the token legend reading ‘Liberty under Law’. Marianne is holding the

Liberty cap, with a cockerel, an emblem of the French Revolution at her elbow. The

date is given as ‘l’an III’, which runs from Jan 1st 1791 to Jan 1st 1792 and is not, as would be

expected, the years since the Revolution. On the reverse we have that it is to

be exchanged for 50 Assignats, a paper currency issued after the Revolution. Surprisingly,

it could be exchanged at most of the major cities in France. It is quite a common

token and Mick thought that it was only produced in copper, in style probably

based on the designs of Dupre. In 1792 (I’an IV) the two sol token had a near identical obverse but the reverse

had changed, with no mention of the assignats, which by now were worthless. It

also had the legend ‘Revolution Francaise’. Mick

pointed out that copper versions of the 1792 token exist but all the ones he

has seen are bronze. This led him to deduce that they were probably made as

keepsakes or specially made for collectors. He believes the copper ones are

exceedingly rare as he believes they would have been melted down.

The

first token to be issued was the two sols (florin size) which contained several

revolutionary ‘signals’. We see Marianne, who

signifies Freedom, Equality and Justice, seated on a tablet which reads ‘The Rights

of Man’, the token legend reading ‘Liberty under Law’. Marianne is holding the

Liberty cap, with a cockerel, an emblem of the French Revolution at her elbow. The

date is given as ‘l’an III’, which runs from Jan 1st 1791 to Jan 1st 1792 and is not, as would be

expected, the years since the Revolution. On the reverse we have that it is to

be exchanged for 50 Assignats, a paper currency issued after the Revolution. Surprisingly,

it could be exchanged at most of the major cities in France. It is quite a common

token and Mick thought that it was only produced in copper, in style probably

based on the designs of Dupre. In 1792 (I’an IV) the two sol token had a near identical obverse but the reverse

had changed, with no mention of the assignats, which by now were worthless. It

also had the legend ‘Revolution Francaise’. Mick

pointed out that copper versions of the 1792 token exist but all the ones he

has seen are bronze. This led him to deduce that they were probably made as

keepsakes or specially made for collectors. He believes the copper ones are

exceedingly rare as he believes they would have been melted down.

Next we had the 5 sols coin from 1791 (crown size), whose obverse shows the national guard, saluting the constitution. This is copied from a Dupre medal commemorating the 1st anniversary of the “Oath of the Federation” 14th July 1790. Other details in the obverse are two broken parchments at the bottom, one for the Church and the other for nobility, indicating their loss of power. Also as part of the design is a shield with three ‘fleurs de lis’, which is the King’s badge, indicating that although he was still around (at this point) he was only a constitutional Monarch, he also had no power. The legend reads ‘VIVRE LIVRES OU MOURIR” (Live free or die), a revolutionary statement. The reverse is fairly similar to the 2 sols, proclaiming it can be exchanged for assignats, with the date underneath. A rare version exists which has the date at 10 O’clock.

After

that we had the King’s Oath Constitutional medal. On the obverse the King is

shown standing right, swearing to be faithful to the nation and the law at the

Constitutional Assembly on the 13 September 1791, with his hand on the constitution.

On the pedestal we have the liberty cap, symbol of the revolution and a fasces, representative of power. The lady in the

background holding a pair of scales represents Equality and the lady on the left

is Minerva, the goddess of wisdom. On the reverse the message is ‘the wish of

the people is no longer in doubt, I accept the constitution’, further showing

that the King has no power. At the bottom of the pedestal are the initials ‘D.

F.’ . A search of the internet found a different

example, where it is spelled out as ‘Dupre F.’. The 5 sols coin for 1792 is

virtually identical to that for 1791, with the change to ‘l’an

iv’, although there is an error reverse with ‘l’an iii’. Possibly it was the engraver who made an error,

having not realised that calendar years were being used. The error is quite

scarce.

After

that we had the King’s Oath Constitutional medal. On the obverse the King is

shown standing right, swearing to be faithful to the nation and the law at the

Constitutional Assembly on the 13 September 1791, with his hand on the constitution.

On the pedestal we have the liberty cap, symbol of the revolution and a fasces, representative of power. The lady in the

background holding a pair of scales represents Equality and the lady on the left

is Minerva, the goddess of wisdom. On the reverse the message is ‘the wish of

the people is no longer in doubt, I accept the constitution’, further showing

that the King has no power. At the bottom of the pedestal are the initials ‘D.

F.’ . A search of the internet found a different

example, where it is spelled out as ‘Dupre F.’. The 5 sols coin for 1792 is

virtually identical to that for 1791, with the change to ‘l’an

iv’, although there is an error reverse with ‘l’an iii’. Possibly it was the engraver who made an error,

having not realised that calendar years were being used. The error is quite

scarce.

Returning

to the tokens two more reverses are known, one saying ‘5 sols’ and another,

with a ‘Revolution Francaise’ similar to the 2 sol reverse. This latter is in bronze. Yet another variant

is the Hercules obverse. Hercules is shown sitting on the lion skin, trying to

break a fasces, which he is plainly failing to do. The

legend reads ‘The French united are invincible’. It is made in both copper and

bronze. After the storming of the Tulleries in August

1792 the first Republic was created and in September and the notorious blood

bath began. Almost immediately, a decree was issued prohibiting the issue of

tokens. Hence the next piece is somewhat of a curio. It is a Hercules design, very

similar to before but Hercules is shown with the King’s sceptre and he has clearly

snapped it in two, alluding to the likely fact that Louis had lost his head by

this time. The piece is the same size as the 2 sols but has no value on it. It

has various representative items such as an owl, signifying wisdom. On the

reverse is a pyramid. Mick believes this is meant to allude to the revolution

being long lived. They are generally made of bronze and some people think they

would have passed as tokens but Mick reckons not. The

reverse legend confirms it to be the first year of the Republic of Gaul, with

the year given as 1792.

Returning

to the tokens two more reverses are known, one saying ‘5 sols’ and another,

with a ‘Revolution Francaise’ similar to the 2 sol reverse. This latter is in bronze. Yet another variant

is the Hercules obverse. Hercules is shown sitting on the lion skin, trying to

break a fasces, which he is plainly failing to do. The

legend reads ‘The French united are invincible’. It is made in both copper and

bronze. After the storming of the Tulleries in August

1792 the first Republic was created and in September and the notorious blood

bath began. Almost immediately, a decree was issued prohibiting the issue of

tokens. Hence the next piece is somewhat of a curio. It is a Hercules design, very

similar to before but Hercules is shown with the King’s sceptre and he has clearly

snapped it in two, alluding to the likely fact that Louis had lost his head by

this time. The piece is the same size as the 2 sols but has no value on it. It

has various representative items such as an owl, signifying wisdom. On the

reverse is a pyramid. Mick believes this is meant to allude to the revolution

being long lived. They are generally made of bronze and some people think they

would have passed as tokens but Mick reckons not. The

reverse legend confirms it to be the first year of the Republic of Gaul, with

the year given as 1792.

Just over 3.65 million of each denomination were struck in just under a year = around 180 tons in total. Quite a feat since minting the 5 Sols wrecked Boulton’s minting machine. Mick pointed out that while this means they should be quite common, huge numbers of them were melted down. Bronzed prooflike specimens (not rare) were most likely made for collectors. Some bronze specimens, especially the Hercules 1 & 2 Sols, are probably Victorian re-strikes circa 1860+ and are quite common.

We are very grateful to Mick for a well researched and presented talk given at short notice.

Future Events.

·

Midland Coin Fair – National Motorcycle Museum – December 10th.

Past Events

- Ten years ago - Collecting 17th century tokens by

feature by

David Powell

- Twenty Years ago -

Images of the Emperor on Byzantine coins by Barrie Cooke

- Thirty years ago –

Toilet Tokens by Ralph Hayes

- Forty years ago –

We had a video on metal detecting

- Fifty years ago –

Club Auction

Club Secretary.